It began like so many true crime stories do — with whispers. A missing woman here, another unexplained disappearance there. No one could see the dark thread connecting them. But in the late 1990s, as America embraced the internet as a new frontier of connection, one man was quietly using it for something far more sinister. His name was John Edward Robinson, and he would soon become known as the country’s first internet serial killer.

To his neighbors in Olathe, Kansas, Robinson was the picture of a respectable man. A husband, a father, a local businessman with a warm smile and a polite wave. He attended community events, spoke with confidence, and projected the image of someone trustworthy. But that image was carefully crafted, a costume he wore with precision. Behind closed doors, Robinson was a manipulator, a predator, and a man with an unquenchable hunger for control.

It was the dawn of online chat rooms and personal ads, a time when meeting strangers through a computer screen felt exciting and new. Few understood the dangers lurking behind usernames and profile pictures. Robinson understood them all too well. He realized that the anonymity of the internet could be a perfect hunting ground — a place where vulnerable people shared their hopes, dreams, and loneliness with strangers who might not be who they seemed.

In the mid-90s, Robinson began trolling BDSM forums, looking for women who were curious about power dynamics or seeking new relationships. He posed as a wealthy businessman, sometimes as a mentor, sometimes as a romantic partner. He promised jobs, housing, and stability. And for women facing desperate circumstances, those promises sounded like salvation. They had no way of knowing they were stepping into a trap.

One of his earliest known victims was a woman named Sheila Faith, who moved to Kansas with her disabled teenage daughter after Robinson promised her a better life. Both mother and daughter vanished without a trace. For years, no one could find them. Friends believed they had simply relocated. Authorities had no evidence of foul play. But Robinson knew exactly what had happened.

The disappearances began to pile up — Beverly Bonner, a prison librarian who left her job and family after becoming involved with Robinson; Suzette Trouten, a nurse from Michigan who dreamed of traveling the world with her new “employer.” Each story followed the same chilling pattern: an online meeting, a series of promises, and then silence. The women’s families were left with unanswered phone calls, unopened letters, and the growing dread that something had gone terribly wrong.

Robinson’s skill as a con man made him all the more dangerous. He forged documents, fabricated backstories, and kept meticulous control over the narrative. In one particularly cruel twist, he continued to cash benefit checks belonging to his victims, forging their signatures to keep the money flowing long after they were gone. The women weren’t just missing — they had been erased from the world, their identities stolen and their voices silenced.

But the façade couldn’t last forever. In 2000, police began to piece together a clearer picture of Robinson’s activities. A missing persons report on Suzette Trouten led investigators to his home and storage facilities. What they found would shatter the quiet suburban image forever. In metal barrels hidden away on his property, they discovered the remains of Trouten and another victim. In a storage locker in Missouri, more barrels — each containing the decomposing body of a missing woman.

The gruesome discovery horrified the nation. It wasn’t just the number of victims that chilled people, but the calculated way Robinson had gone about his crimes. He had weaponized charm, technology, and opportunity, exploiting the trust of vulnerable women in the most personal way. The internet was supposed to connect people; for Robinson, it was a tool for killing.

During interrogations, Robinson remained calm, even smug. He insisted on his innocence, hinting at elaborate conspiracies and mysterious enemies. But prosecutors had mountains of evidence — DNA matches, forged contracts, email records linking him directly to the victims. The case was airtight, and Robinson’s arrogance couldn’t save him.

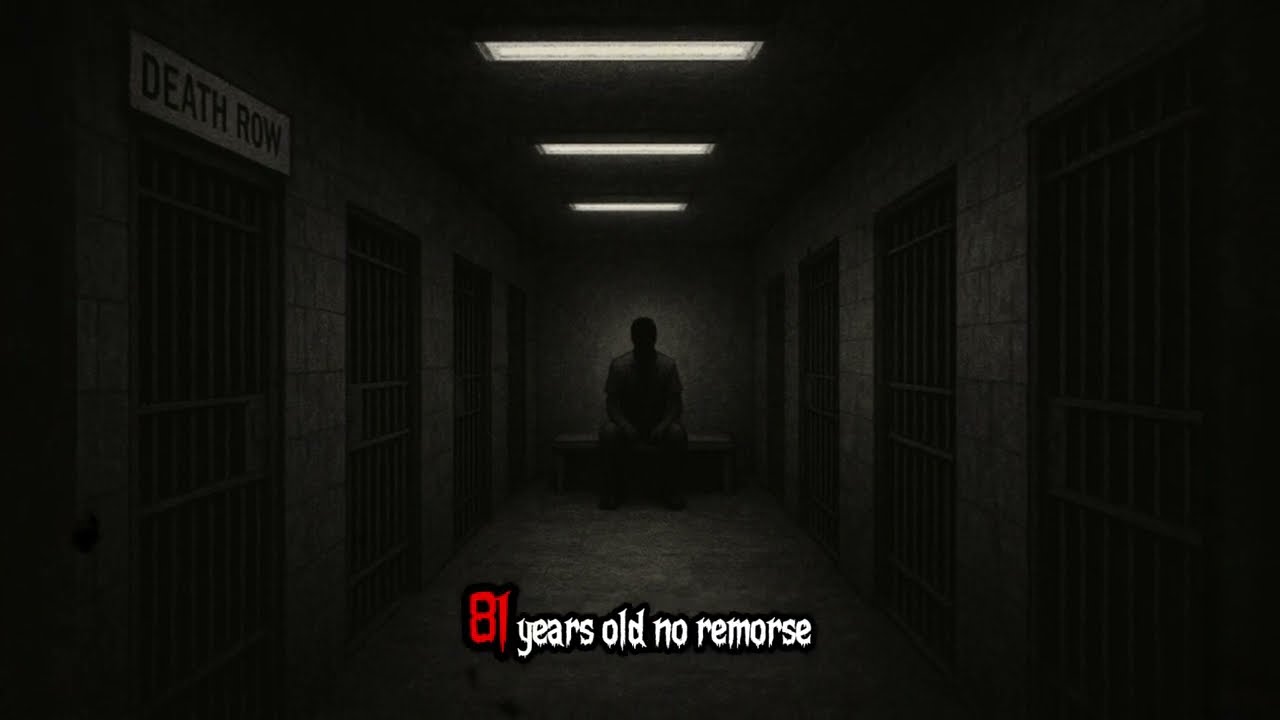

In 2003, John Robinson was convicted of multiple counts of murder and sentenced to death in Kansas. He also received life sentences in Missouri after striking a deal to avoid the death penalty there. Even behind bars, he has remained an enigma — refusing to admit to all of his suspected crimes, keeping secrets that may never be uncovered.

Law enforcement believes Robinson may be responsible for many more deaths than the eight he is officially linked to. His ability to operate across state lines, combined with his habit of targeting women who were socially or economically vulnerable, means there could be dozens of families still wondering what happened to their loved ones. For those families, closure remains elusive.

The case of John Robinson changed the way investigators looked at online interactions. It was a wake-up call in the early days of the internet — a reminder that behind a friendly message could lurk a dangerous predator. New safety measures, public awareness campaigns, and improved digital forensics emerged in the wake of his arrest. But the damage had already been done.

In prison, Robinson is known to spend his days quietly, often avoiding conversations about his past. Former detectives who worked his case say he is still manipulative, still calculating. They suspect he enjoys the fact that not all his crimes have been uncovered — that he holds onto that final piece of control.

For the families of his victims, the horror is twofold: the loss of their loved ones and the knowledge of how cruelly they were deceived. Many of the women trusted Robinson not just with their time, but with their hopes for a better life. To have those hopes twisted into a fatal trap is a wound that may never heal.

Suzette Trouten’s mother once said in an interview that she couldn’t comprehend the evil it took to lure someone in with kindness, only to destroy them. She hoped Robinson would one day confess fully, not for his sake, but for the sake of those left behind. So far, that hope remains unanswered.

As technology advances, new predators emerge, but Robinson’s story still resonates. It stands as a cautionary tale about trust, about the dangers of anonymity, and about how even the most ordinary-looking person can harbor extraordinary darkness. The internet may have changed, but human nature hasn’t.

Today, the barrels have been emptied, the storage lockers cleared, and the crime scenes dismantled. But the shadow of John Robinson lingers. His name is etched into the dark history of American crime — a reminder that the most dangerous predators are often the ones you never see coming.

In the end, Robinson’s mask slipped, but only after years of deception. By then, too many lives had been stolen, too many families left in pieces. The country had been plunged into horror, and even now, decades later, the echo of that fear remains.

It is that echo — the lingering unease — that keeps his story alive. Not as a morbid curiosity, but as a warning: trust is fragile, danger can hide in plain sight, and the click of a mouse can be the start of a nightmare.

For John Edward Robinson, the internet was not a window to the world. It was a hunting ground. And for his victims, the connection they thought would bring them closer to a better life led them straight into the hands of a killer.

News

Watch What Happens When an Arrogant Chef Disrespects the Owner’s Mother

The kitchen at La Belle Cuisine was alive with a frenzy of activity. It was Friday evening, the busiest night…

What Happens When a Pregnant Woman Faces Racism in Public – The Observer’s Reveal Will Stun You

The afternoon sun filtered through the windows of the crowded city bus, casting streaks of light over weary faces and…

Racist Police Chief Arrests Black Girl Selling Lemonade, But Her Father’s Identity Changes Everything

The summer sun beat down mercilessly on the quiet suburban street, where the scent of freshly cut grass mixed with…

Humiliation Turns Into Surprise: Black Nurse Exposes Doctor’s Arrogance in Front of an Unexpected Guest

The hospital corridor buzzed with its usual rhythm. Nurses and doctors moved briskly from room to room, patients murmured from…

You Won’t Believe What Happened When Cops Arrived for a Homeless Veteran

Harold Jenkins had worked at the corporate office of SilverTech Industries for over forty years. His hands, calloused and scarred…

Racist Karen Tried to Ruin His Day—But Watch How Justice Unfolded

Chapter 1: Life on the StreetsJohn “Jack” Harper had served two tours in Afghanistan and one in Iraq. After returning…

End of content

No more pages to load