It was a crisp autumn evening in 1956 when a small American town was shaken by a brutal crime that no one could have imagined. The murder of a young woman would haunt the community for generations, lingering like a shadow over families, neighbors, and investigators.

The victim, 23-year-old Mary Ellen Davis, was known for her kindness, her bright smile, and her dreams of becoming a schoolteacher. She had been walking home from church choir practice when her life was violently stolen.

When police discovered her body in a wooded area not far from her home, the town went silent with fear. Newspapers splashed headlines about the tragedy, and whispers filled the streets.

Detectives worked tirelessly in the days and weeks that followed. They interviewed dozens of townspeople, collected fingerprints, and gathered fibers and blood samples using the forensic tools of the 1950s. But despite their efforts, the case quickly hit a dead end.

In that era, DNA technology didn’t exist. What today seems like routine analysis was impossible for investigators of the time. They had only microscopes, ink fingerprints, and the power of observation.

Among the evidence collected was a glass microscope slide containing a biological sample. Detectives stored it along with other items, never realizing that decades later, that tiny piece of glass would become the key to unlocking the mystery.

The town mourned, but as weeks turned into months, and months into years, the murder of Mary Ellen faded into the annals of unsolved crimes. Her parents died never knowing who was responsible.

For the next six decades, her name appeared occasionally in local newspapers whenever the town recalled its darkest moments. Each anniversary renewed pain but offered no resolution.

Generations grew up hearing whispers of the “1956 murder” but without answers, the crime became almost a ghost story—one of those tragedies spoken of in hushed tones.

Then came the late 2010s, when forensic science had advanced beyond what anyone in the 1950s could imagine. Cold case units across the country were reopening files, testing old evidence with modern DNA technology.

In 2019, the dusty file of Mary Ellen Davis landed on the desk of Detective Sarah Mitchell, a dedicated investigator known for her relentless pursuit of justice in forgotten cases.

Mitchell combed through the evidence box, examining brittle photos, yellowed reports, and outdated lab notes. And there, wrapped in tissue paper, was the microscope slide.

She immediately recognized the potential. Though more than six decades had passed, DNA could remain preserved in ways once thought impossible. That tiny slide might still carry genetic material from the perpetrator.

The sample was carefully transported to a modern crime lab, where technicians prepared it for testing. Weeks of meticulous work followed, as scientists extracted degraded DNA strands and amplified them with cutting-edge techniques.

Then, one late evening, the results came in. The DNA profile was complete. The slide that had sat untouched for 63 years now carried the identity of the killer.

The profile was uploaded to national databases, and in mere hours, a match appeared. The man responsible was identified: a local resident named Harold Thomas, who had died in the early 1980s.

For detectives, the revelation was both shocking and bittersweet. The killer was no longer alive to face trial, but finally, Mary Ellen’s story had an ending.

Harold Thomas had lived an unassuming life. Records showed he had been questioned in the early investigation but quickly dismissed due to lack of evidence. He married, raised a family, and died without ever being exposed.

The discovery stunned the community. For decades, people had wondered whether the killer still walked among them. Now they knew: he had been there all along, hiding in plain sight.

For Mary Ellen’s surviving relatives, the news brought a complicated mix of emotions. Relief, sadness, anger, and closure collided as they processed the fact that justice had come—though late.

“I never thought I’d live to see this day,” said her niece, who had been a toddler in 1956. “We finally know who did it. We finally know what happened.”

Detective Mitchell described the moment as one of the most powerful in her career. “This case proves that no matter how much time passes, science has the power to speak for victims who can no longer speak for themselves.”

The breakthrough drew national headlines. Journalists marveled at how a simple microscope slide, forgotten for decades, became the silent witness that cracked the case.

Experts highlighted the importance of preserving evidence, even when cases seem hopeless. What detectives in 1956 couldn’t imagine, technology in 2019 made possible.

The case also underscored the evolution of forensic science—from fingerprint dusting and magnifying glasses to DNA sequencing and genetic genealogy.

For the community, it was a lesson in perseverance. Justice may be delayed, but with determination, it is never entirely lost.

Historians documented the case as one of the oldest cold cases ever solved by DNA, placing it alongside other landmark breakthroughs in forensic history.

The discovery inspired renewed efforts across the country to reopen other cold cases. Families with long-forgotten tragedies began to hope again.

Forensic experts used the case as a teaching tool, showing new generations of investigators that even the smallest trace of evidence could hold answers for decades.

The memory of Mary Ellen Davis was finally honored in a way that felt complete. Her grave, once a symbol of unanswered questions, became a place of closure and reflection.

On the anniversary of her death in 2020, the town held a memorial service. People gathered not to grieve, but to celebrate that truth had prevailed, even after 63 long years.

Candles were lit, prayers were said, and for the first time, the story ended not with despair, but with justice.

Detective Mitchell spoke at the ceremony. “Mary Ellen was denied justice in 1956, but today, we give her what was taken. The truth has a way of surviving, waiting for the day it will be heard.”

The microscope slide, once just a forgotten piece of glass, is now preserved in the state’s forensic museum, a testament to persistence and the power of science.

Mary Ellen’s story continues to inspire law enforcement and families alike. It serves as proof that even when decades pass, answers are still possible.

In the end, the case reminds us that justice is not bound by time. It may be delayed, it may be hidden, but it waits—like the DNA on that fragile slide—for someone to find it.

And when it is found, it changes everything.

News

Watch What Happens When an Arrogant Chef Disrespects the Owner’s Mother

The kitchen at La Belle Cuisine was alive with a frenzy of activity. It was Friday evening, the busiest night…

What Happens When a Pregnant Woman Faces Racism in Public – The Observer’s Reveal Will Stun You

The afternoon sun filtered through the windows of the crowded city bus, casting streaks of light over weary faces and…

Racist Police Chief Arrests Black Girl Selling Lemonade, But Her Father’s Identity Changes Everything

The summer sun beat down mercilessly on the quiet suburban street, where the scent of freshly cut grass mixed with…

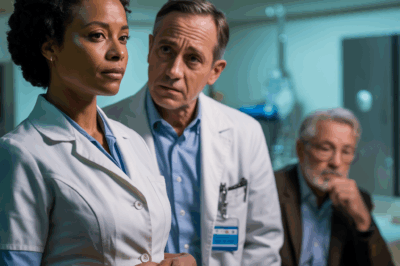

Humiliation Turns Into Surprise: Black Nurse Exposes Doctor’s Arrogance in Front of an Unexpected Guest

The hospital corridor buzzed with its usual rhythm. Nurses and doctors moved briskly from room to room, patients murmured from…

You Won’t Believe What Happened When Cops Arrived for a Homeless Veteran

Harold Jenkins had worked at the corporate office of SilverTech Industries for over forty years. His hands, calloused and scarred…

Racist Karen Tried to Ruin His Day—But Watch How Justice Unfolded

Chapter 1: Life on the StreetsJohn “Jack” Harper had served two tours in Afghanistan and one in Iraq. After returning…

End of content

No more pages to load